Hem | Om mig | Musik | Recept | Foto | Konst | Platser | Kemi | Eget skrivande | Texter | Tänkvärt | Humor | Filmklipp | Länkar | Ladda ner

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart

På skivbolaget Deccas märke L’Oiseau-Lyre gjordes den första inspelningen av Mozarts symfonier på tidstrogna instrument i slutet på 1970-talet och i början av 1980-talet. Inspelningarna gavs ut i sju volymer. Mozart-forskaren Neal Zaslaw var rådgivare till projektet och skrev även kommentarerna till inspelningarna. Dessa kommentarer har jag sammanställt och redigerat och gjort tillgängliga tillgängliga nedan. Texten finns även som ett pdf-dokument.

The Symphonies

Mozart’s earliest symphonies

The London Symphonies

Leopold Mozart realised early that he had on his hands what he later referred to as “the miracle that God permitted to be born in Salzburg”. Acting with vigour and imagination to carry out what he conceived to be a sacred trust, he virtually abandoned the furtherment of his own career in order to devote himself to his son’s education. This meant, among other things, that from January 1762 when little Wolfgang was just turning six, the Mozart family was frequently on the road, visiting the courts and musical centres of western Europe. These trips were intended to raise money, to spread the fame of the infant prodigy, and to educate Wolfgang by exposing him to the important music and musicians of the day. Thus it was that toward the end of April 1764 the Mozarts found themselves in London. By the beginning of August the eight-year-old Wolfgang had to his credit some four-dozen unpublished keyboard pieces, as well as three collections published in Paris and London containing ten sonatas for keyboard with violin. How he came to write his first symphony was recalled in the years following his death by his sister Nannerl, herself a precocious keyboard player who was thirteen at the time:

“On the 5th of August [we] had to rent a country house in Chelsea, outside the city of London, so that father could recover from a dangerous throat ailment, which brought him almost to death’s door ... Our father lay dangerously ill; we were forbidden to touch the keyboard. And so, in order to occupy himself, Mozart composed his first symphony with all the instruments of the orchestra, especially trumpets and kettledrums. I had to copy it as I sat at his side. While he composed and I copied he said to me, ‘Remind me to give the horn something worthwhile to do!’ ... At last after two months, as father had completely recovered, [we] returned to London.”

Leopold and his family moved back to London around the end of September, and Wolfgang and Nannerl resumed their round of public and private concerts and appearances at Court, while Wolfgang received instruction in singing from the Italian castrato Giovanni Manzuoli. From 6 February 1765 notices appeared in London newspapers for a “Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Music” for the benefit of “Miss MOZART of Twelve and Master MOZART of Eight Years of Age; Prodigies of Nature”. (Note that Leopold misrepresented his children’s ages.) On 8 February Leopold wrote to his Salzburg friend, patron and landlord. Lorenz Hagenauer:

“On the evening of the 15th we are giving a concert, which will probably bring me in about one hundred and fifty guineas. Whether I shall still make anything after that and, if so, what, I do not know .... Oh, what a lot of things I have to do. The symphonies at the concert will be by Wolfgang Mozart. I must copy them myself, unless I want to pay one shilling for each sheet. Copying music is a very profitable business here.”

The concert was postponed until Monday the 18th, however, because a performance of Thomas Arne’s oratorio Judith had been put back from the 7th to the 15th, tying up some artists upon whose services the Mozarts had counted. A second postponement occurred for unstated reasons. From 15th February notices appeared in London newspapers reading:

'HAYMARKET, Little Theatre.

THE CONCERT for the Benefit of Miss and

Master MOZART will be certainly

performed on Thursday the 21st instant, which

will begin exactly at six,

which will not hinder the Nobility and Gentry

from meeting in other Assemblies

on the same Evening.

Tickets to be had of Mr. Mozart,

at Mr. Williamson’s in

Thrift-street, Soho, and at the said Theatre.

Tickets delivered for the 15th will be admitted.

A Box Ticket admits two into the Gallery.

To prevent Mistakes, the Ladies and Gentlemen

are desired to send their

Servants to keep Places for the Boxes, and give

their Names to the Boxkeepers

on Thursday the 21st in the Afternoon.

The notices published on the day of the concert contained an additional sentence: “All the Overtures [i.e., symphonies] will be from the Composition of these astonishing Composers, who are only eight Years old.” (An error made Wolfgang and Nannerl the same age and both composers.) Some weeks later Leopold sent Hagenauer a report of Wolfgang’s symphonic debut, which, disappointingly for us, dealt with financial rather than artistic matters:

“My concert, which I intended to give on February 15th, did not take place until the 21st, and on account of the number of entertainments (which really weary one here) was not so well attended as I had hoped. Nevertheless, I took in about a hundred and thirty guineas. As, however, the expenses connected with it amounted to over twenty-seven guineas, I have not made much more than one hundred guineas.”

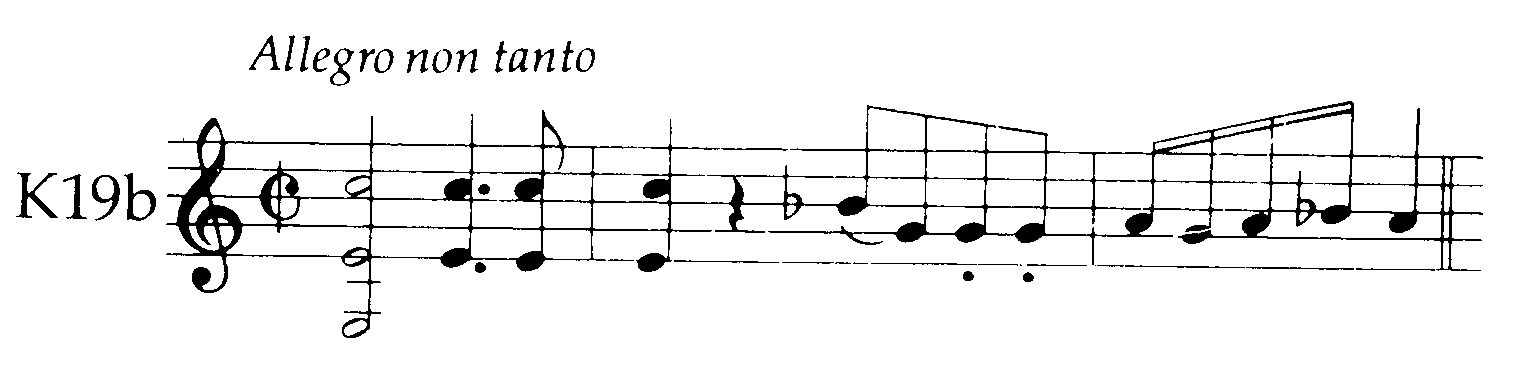

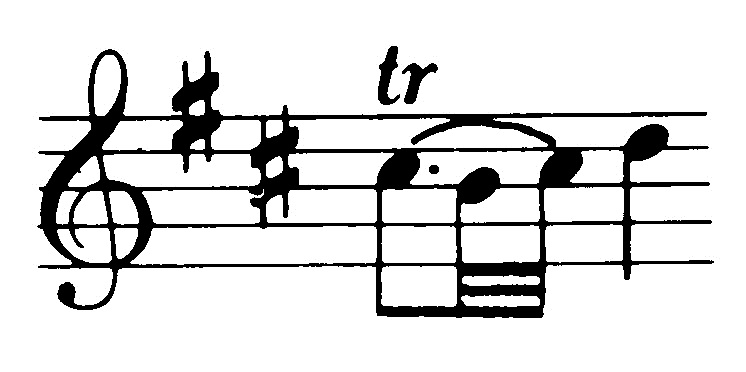

The programme of 21 February 1765 has not come down to us, but extrapolating from programmes preserved from similar occasions, we can make an educated guess about the shape of the event. Concerts began and ended with symphonies, which might also have been used to complete the first half, to launch the second, or to serve both purposes. Between the symphonies there would have been performances on the harpsichord or chamber organ by Wolfgang and Nannerl, together and separately, improvised and prepared. Some of London’s favourite instrumentalists and singers would have contributed solos, as was the custom at benefit concerts. (We know which of the virtuosos active in London were associated with the Mozarts because Leopold listed their names in his travel diary). The symphonies performed on 21 February 1765 must have been from among K. 16, K. 19, and K. 19a, all of which are thought to date from this period in London. In addition, we should not rule out of consideration the symphony K. 19b, now lost and known only from its incipit in an old Breitkopf catalogue; this is also believed to have been composed by Mozart in London:

From 11 March a series of notices appeared in London newspapers announcing the Mozarts’ final concert appearance there, on 13 May. The programme again included “all the OVERTURES of this little Boy’s own Composition”.

As early as 19 May 1763 a letter from Vienna had reported that, “... we fall into utter amazement on seeing a boy aged six at the keyboard and hearing him ... accompany at sight symphonies, arias and recitatives at the great concerts ...” That Wolfgang was not only able to direct his own symphonies from the keyboard but that he did so in London, is confirmed by one of Leopold’s newspaper announcements stating that the concert of 13 May would “chiefly be conducted by his Son”.

Mozart’s London symphonies reveal how perfectly the boy had absorbed and could imitate the most up-to-date, galant style of the period. His models were primarily the cosmopolitan group of German-speaking composers active in Paris and London: Johann Gottfried Eckard, Leontzi Honauer. Hermann Friedrich Raupach, Christian Hochbrucker and Johann Schobert in the former city; Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel in the latter. The care with which the little Mozart studied one of Abel’s symphonies is indicated by the fact that he copied it out himself. More than a century later, the existence of Mozart’s manuscript of Abel’s symphony caused it to be published in the old Complete Works as one of Mozart’s own early symphonies (the Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, formerly K. 18, now K. Anh. A51).

Though there is no evidence for the assertion that Mozart received formal instruction from J. C. Bach, the two were closely associated in London and the music of the older man influenced the younger throughout his career. J. C. Bach was one of the few musicians about whom only praise appears in the Mozart family correspondence. When Bach died, Mozart paid him tribute in the slow movement of the piano concerto, K. 414/385p, and when Abel died he did likewise in the finale of the violin sonata, K. 526 – in each case basing his memorial on a work by the man whom he wished to honour.

We do not know the make-up of the undoubtedly modest orchestra that Leopold Mozart assembled for the concerts of 21 February and 13 May 1765, but we do have information about other ensembles of the period. We have therefore based our interpretation of Mozart’s three London symphonies on a characteristic small English orchestra of the mid-1760s: the strings 6-5-2-2-1, with the necessary wind (pairs of oboes and horns) as well as harpsichord continuo and a bassoon doubling the bass line.

Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, K. 16

1. Allegro molto

2. Andante

3. Presto

The manuscript score of this work is found in the collection that was in Berlin until World War II and is now at Kraków. Unlike several other very early works which are in his father’s hand, this one is in Wolfgang’s. At the top of the first page is written Sinfonia, di Sig. Wolfgang Mozart a london 1764. The manuscript begins tidily, as if intended to be a fair copy, but extensive corrections were then entered by Mozart in a larger, cruder hand, creating the appearance of work-in-progress. This symphony has always been considered Mozart’s first, but can it really be the one described in Nannerl’s account? As we have seen, Nannerl mentioned that she copied the symphony and that it called for trumpets and kettledrums, neither condition applying here. Of course, many symphonies of the third quarter of the eighteenth century did circulate shorn of their trumpet and kettledrum parts, which were often considered optional and sometimes separately notated and absent from the score. Mozart’s usual trumpet keys were C, D, and E flat major, so this symphony could indeed have included those instruments. Furthermore, one might speculate that perhaps Nannerl did copy a score but that Wolfgang so throughly revised it that it became illegible, forcing him to make another copy – the one we now have – before continuing his revisions.

Another fact, the meaning of which is still unclear, is that the cover for the original parts to the Symphony in D major, K. 19, has notations on it, in Leopold’s hand, indicating that it had originally served first as the cover for parts to a symphony in F major (presumably K. 19a) and then for parts to one in C major (presumably the missing K. 19b) – but there is no mention of a symphony in E flat. As for giving the horn “something worthwhile to do”, that is perhaps satisfied by the passage in the andante of K. 16 where the horn plays the motive do-re-fa-mi, known to everyone from the finale of Mozart’s Jupiter symphony. Considering all of the evidence, however, we are forced to conclude that the E flat symphony K. 16, is probably not the work described in Nannerl’s anecdote, and that Mozart’s “first” symphony must be lost.

The first movement of K. 16 opens with a three-bar fanfare in octaves, immediately contrasted with a quieter eight-bar series of suspensions, all of which is repeated. This leads to a brief agitato section, and the first group of ideas is brought to a close by a cadence on the dominant. At this point the wind fall silent and we hear the initial idea of the second group, which is extended by a passage of rising scales in the lower strings accompanied by tremolo in the violins. A brief coda concludes the exposition, which is repeated. The second half of the movement, also repeated, covers the same ground as the first, working its way through the dominant (B flat) and the relative minor (C) to reach the tonic (E flat) only at the beginning of the second group.

The andante – a binary movement in C minor – is a remarkably successful bit of atmospheric writing. The sustained wind, the mysterious triplets in the upper strings, and the stealthy duplets in the bass instruments, combine to create a scene that would have been perfectly at home in an opera of the period, perhaps to accompany a clandestine nocturnal rendezvous.

With the beginning of the presto, the sun rises and another fanfare launches us into a vigorous jig-like finale in the form of a simple rondo. The refrain of the rondo is committedly diatonic in character, but the intervening episodes are filled with delightfully piquant touches of chromaticism in the latest, most galant manner.

Those writers who have been at considerable pains to point out the great differences in length, complexity and originality between this earliest surviving symphony of Mozart and his last, may have missed a crucial point: there is little difference in length, complexity or originality between Mozart’s K. 16 and the symphonies of J. C. Bach’s opus 3 and Abel’s opus 7, which he took as his models.

Symphony No. 4 in D major, K. 19

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Presto

This symphony survives in the Bavarian State Library in Munich as a set of orchestral parts in Leopold Mozart’s hand, in the cover mentioned in the discussion of K. 16. The manuscript also contains what is described in the Mozart literature as a “keyboard reduction” of the second and third movements written in a childish hand. It is disputed whether or not this “keyboard reduction” may have been the original notation from which those movements were subsequently orchestrated, and whether or not the unidentified hand may be Nannerl’s.

The first movement opens with the kind of fanfare, used for signalling by posthorns or military trumpets, which never returns. The timbre of the movement is noticeably brighter than that of the previous symphony, due to the resonance that D major gives to the strings. The movement proceeds on its extroverted way, in a kind of march tempo, with no repeats. An especially nice touch is the unanticipated A sharp with which the development section begins.

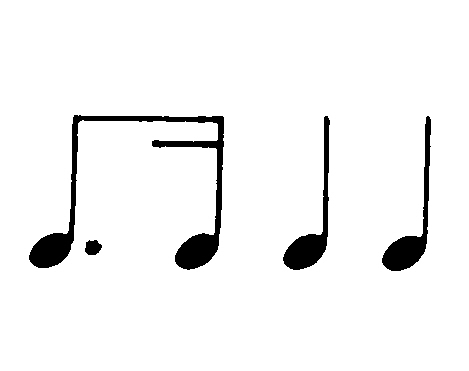

The andante in G major 2/4 evokes a conventional, pastoral serenity. Its “yodelling” melodies and droning accompaniments were undoubtedly intended to evoke thoughts of hurdy-gurdies and bagpipes. The finale, 3/8, although marked presto as in the previous symphony, is however not quite as rapid, as the presence of demisemiquavers reveals. It is an energetic binary movement with both halves repeated. An occasional “yodelling” in the melody ties it to the previous movement.

Symphony in F major, K. 19a

1. Allegro assai

2. Andante

3. Presto

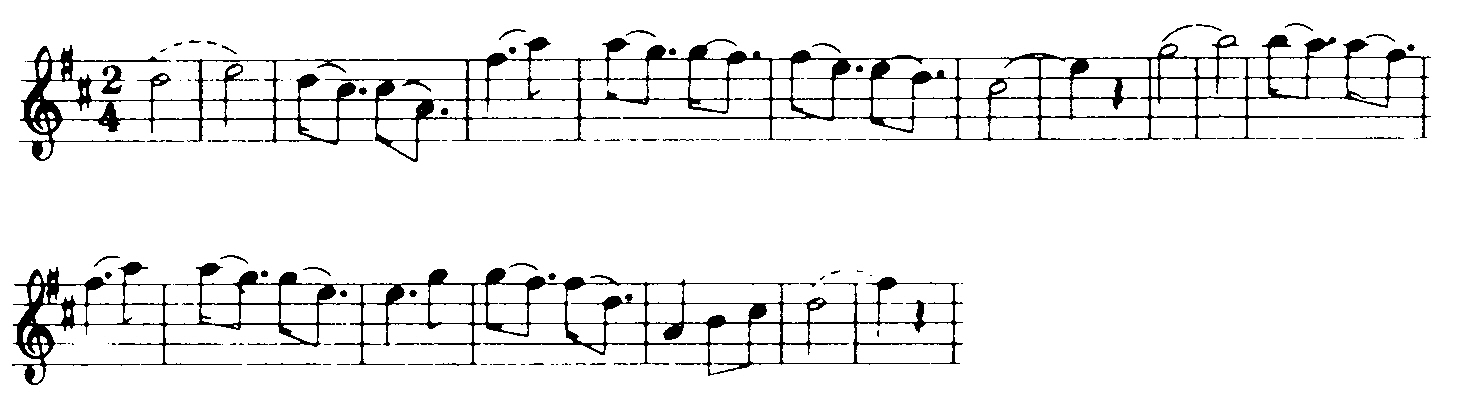

At the beginning of February 1981 Mozart lovers were surprised and delighted to read in their newspapers press dispatches from Munich describing the rediscovery of a lost Mozart symphony. A set of parts in Leopold Mozart’s hand, found among some private papers, proved to be the Symphony in F major, K. 19a, the existence of which had been known from the incipit of its first movement, which was notated on the cover of the Symphony in D, K. 19, discussed above. That K. 19a was a completed work and not a fragment had also been known, because its incipit occurred in an early-nineteenth-century Breitkopf & Härtel catalogue of manuscripts, with an indication that the work was for strings and pairs of oboes and horns. The newly-discovered parts were acquired by the Bavarian State Library, and the work has now been published. It was given its modern British première by the Academy of Ancient Music in a BBC broadcast of 2 August 1981. Thus a stroke of good fortune restores to us a work from Mozart’s London sojourn thought to be irretrievably lost.

Leopold entitled the work, Sinfonia in F/à/2 Violinj/2 Hautb:/2 Cornj/Viola/e/Basso/di Wolfgango Mozart/compositore de 9 Anj. As Mozart turned nine years old on 27 January 1765, the creation of the symphony must be placed after that date but in time for either the concert of 21 February or that of 13 May. Quite exceptionally for Mozart’s symphonies, the basso part is figured throughout – that is, numerical symbols indicating which chords to play have been provided for the continuo harpsichordist. (The score of K. 16 has a very few figures in its first movement and none in the rest; the other symphonies are unfigured.)

The first movement, allegro assai in common time, opens with a broad melody in the first violins, accompanied by sustained harmonies in the winds, broken chords in the inner voices, and repeated notes in the bass instruments. A brief but effective bit of imitative writing then leads to a cadence on the dominant and the introduction of a contrasting “second subject”. Tremolo in the upper strings accompanying a triadic, striding bass line carries us to the closing subject. The second half of the movement presents the same succession of ideas as the first, and both halves are repeated. As the harmonic movement is from tonic to dominant in the first half, and from dominant to tonic in the second, with little that could be described as “developmental” in the use of themes or harmonies, the form is closer to simple binary form than to sonata form as it is generally understood.

In the second movement, andante 2/4 in B flat major, the oboes are silent. Like the first movement, this consists of two approximately equal sections, both repeated. Although the texture is simple and the ideas not unconventional, the movement exhibits a polish and élan quite remarkable in the work of a child.

The finale is a rondo, marked presto 3/8. Finales in 3/8, 6/8, 9/8, or 12/8 were extremely common at the time this work was written, and usually took on the character of an Italianate giga. Here, however, little Wolfgang must have had his eye on pleasing his British public, and the refrain of his rondo has some of the character of a highland fling, bringing the symphony to a suitably jolly conclusion.

The Dutch Symphonies

The Mozarts’ original intention up on leaving London was to return directly to Paris, where they had left some of their luggage. Not long after arriving in London, Leopold had informed Hagenauer, “... we shall not go to Holland, that I can assure her [Hagenauer’s wife]”. However, the Dutch ambassador to the Court of St James sought Leopold out in Canterbury around 25 July 1765, at the beginning of the Mozarts’ return journey. As Leopold later wrote to Hagenauer from The Hague, the ambassador “implored me at all costs to go to The Hague, as the Princess of Weilburg, sister of the Prince of Orange, was extremely anxious to see this child, about whom she had heard and read so much. In short, he and everybody talked at me so insistently and the proposal was so attractive that I had to decide to come ...” The Mozarts remained in Holland from September 1765 to April 1766.

This detour on their homeward journey resulted in performances in Ghent (5 September), Antwerp (7 or 8 September), The Hague (three concerts between 12 and 19 September, *30 September, *22 January), Amsterdam (*29 January, 26 February), the Hague (*mid-March), Haarlem (early April), Amsterdam (16 April), and Utrecht (*21 April). From newspaper announcements, archival documents and correspondence, we learn that at least five of these thirteen performances (indicated by asterisks) included performances of symphonies by Mozart. A typical newspaper announcement is the following, taken from the 'S-Gravenhaegse Vrijdagse Courant:

“By permission, Mr. MOZART, Music master to the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, will have the honour of giving, on Monday, 30 September 1765, a GRAND CONCERT in the hall of the Oude Doelen at The Hague, at which his son, only 8 years and 8 months old, and his daughter, 14 years of age, will play concertos on the harpsichord. All the overtures will be from the hand of this young composer, who, never having found his like, has had the approbation of the Courts of Vienna, Versailles and London. Music-lovers may confront him with any music at will, and he will play everything at sight. Tickets cost 3 florins per person, for a gentleman with a lady 5.50fl. Admission cards will be issued at Mr. Mozart’s present lodgings, at the corner of Burgwal, just by the City of Paris, as well as at the Oude Doelen.”

The “overtures” performed at the Dutch concerts must have been the London symphonies discussed above, and the B flat symphony, K. 22, written in The Hague in December 1765. These works received further performances on the journey homeward to Salzburg. We have more or less certain evidence of symphonies being performed in Paris (sometime between 11 May and 8 July 1766), Dijon (18 July), Lyons (13 August), Lausanne (mid-September), Zurich (7 and 9 October), Donaueschingen (between 20 and 31 October), and finally Salzburg itself where, on 8 December, just over a week after the Mozarts’ triumphal return, “at High Mass in the Cathedral for a great festivity [The Feast of the Immaculate Conception], a symphony was done which not only found great approbation from all the Court musicians, but also caused great astonishment ...”

A list of the orchestral personnel of the Schouwburg Theatre in Amsterdam survives for the year 1768. The orchestra consisted of 3 first and 3 second violinists, 2 violists (both of whom doubled on clarinet), 1 cellist, 1 bass player, 2 oboists (most likely doubling on flute), 1 bassoonist, 2 horn players, 1 harpsichordist, and a supernumerary who played kettledrums when needed – thus a total of 16 or 17 musicians. We have modelled our performance of Mozart’s two Dutch works on this ensemble.

Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, K. 22

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegro molto

At the top of Leopold Mozart’s score of this work, to be found in the State Library, West Berlin, is the inscription Synfonia di Wolfg. Mozart à la Haye nel mese Decembre 1765. Despite the suggestion by several of Mozart’s biographers, it is unlikely that it was written for the installation of William V as Regent of the Netherlands, an event which occurred some three months later (see the notes for the following work). Rather, its creation was probably connected with public performances at The Hague: the Mozarts’ concert there on 30 September must have shown off the London symphonies, and its success led in turn to the concert of 22 January, for which new music would have been required.

The opening allegro in common time is without repeats. It begins with a pedal in the bass for fourteen bars, in a manner associated with the Mannheim symphonists but heard in many parts of western Europe by 1765. The contrasting second subject consists of a dialogue between the first and second violins, followed by the apparently mandatory theme in the bass instruments accompanied by tremolo in the upper strings. A brief but effective development section puts the opening idea through the keys of F minor and C minor, returning to the home key shortly after the reappearance of the second subject, with the rest of the exposition then heard essentially as before.

The G minor andante, 2/4, exhibits surprising intensity of musical gesture, with its brooding chromaticism, imitative textures, and occasional stern unisons. Abert thought that he heard foreshadowings here of the andante of Mozart’s penultimate symphony, K. 550. The movement’s form is a simple A-B-A structure with coda.

As if such intensity of feeling were “dangerous” in a work intended for polite society, the rondo finale makes amends by leaning in the other direction. No tension mars its frothy lightheartedness. Marked allegro molto, 3/8, it has the spirit of a brisk minuet, its opening bringing to mind that of the quartet “Signore, di fuori son già i suonatori” in the finale to the second act of Figaro.

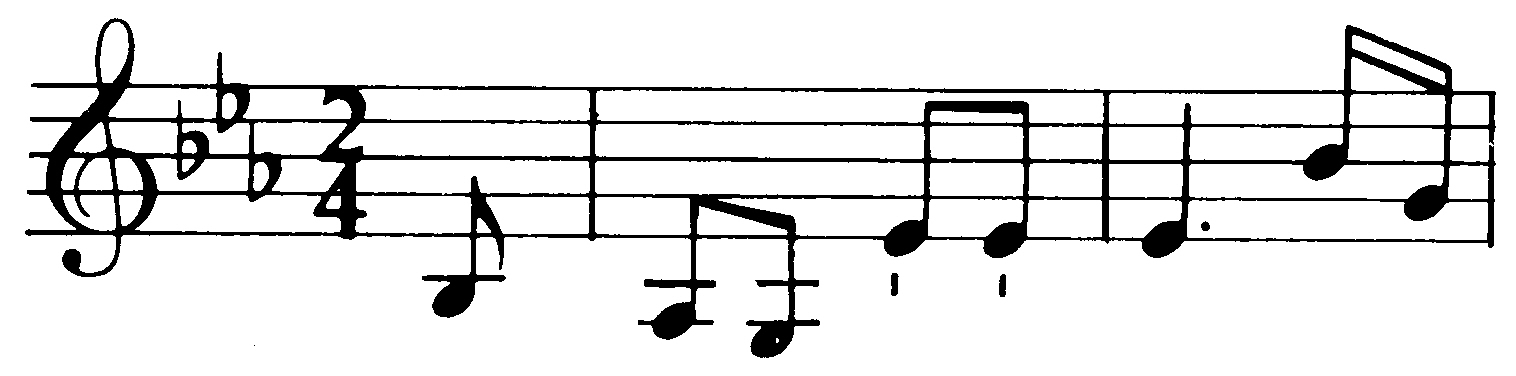

In Leopold’s travel diary he noted two Amsterdam musicians named Kreusser. Johann Adam Kreusser had been leader of the Schouwburg orchestra since 1752, and his younger brother Georg Anton had, from 1759, taken lessons with him while playing in that ensemble. The latter must have heard Mozart’s B flat major symphony, K. 22 (probably as a member of the orchestra that performed it), because he paid it the compliment of stealing the opening of its first movement for his own E flat major symphony, opus 5, no. 4, published in Amsterdam in 1770.

Symphony in D major, K. 32

1. Molto Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Finale

For celebrations connected with the installation of William V, Prince of Orange, as Regent of the Netherlands, the ten-year-old Mozart composed a suite of pieces for small orchestra and obbligato harpsichord, under the title Galimathias musicum, which was performed on 11 March 1766. This was a “quodlibet”; that is, some movements were based on tunes well-known to Mozart and his Salzburg compatriots, and others on tunes familiar to his Dutch audience. The work survives in two versions: a preliminary draft in which Wolfgang’s and Leopold’s hands are found intermingled, and a fair copy apparently made by a professional copyist for a performance in Donaueschingen some months later. From the draft version it seems that Mozart originally thought of the first four movements as forming a kind of miniature introductory sinfonia, and these movements are indeed found together in a nineteenth-century manuscript labelled “sinfonia”. (In the Donaueschingen version the order of the movements has been altered, however, and the introductory sinfonia dispersed. It is the four movements of the preliminary draft that are presented here.

The opening allegro in common time is nothing more than a few happy noises – repeated notes, loud chords, rapid scale passages, and so on – here played twice. The D minor andante in binary form is strangely orchestrated, with the melody in the violas.

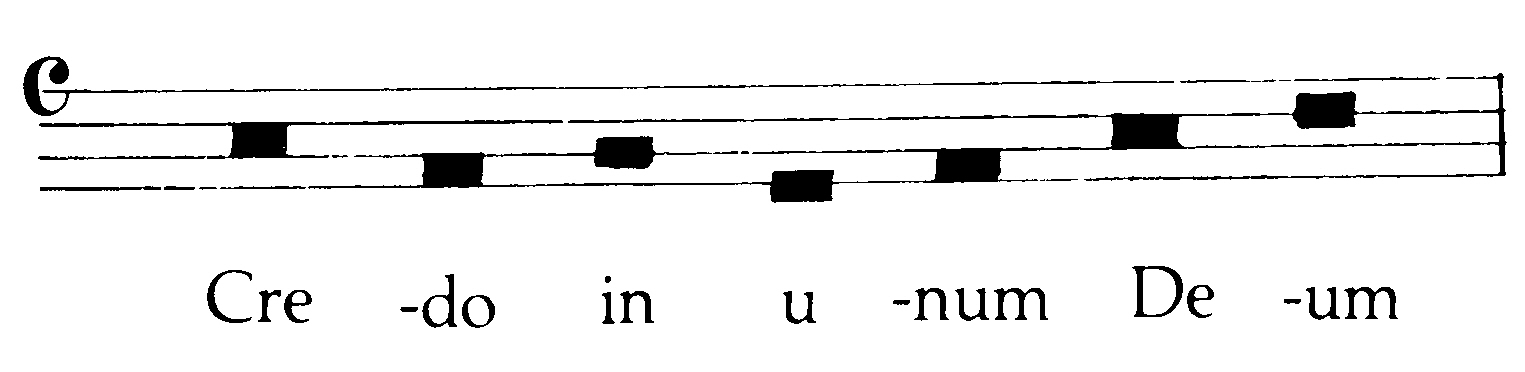

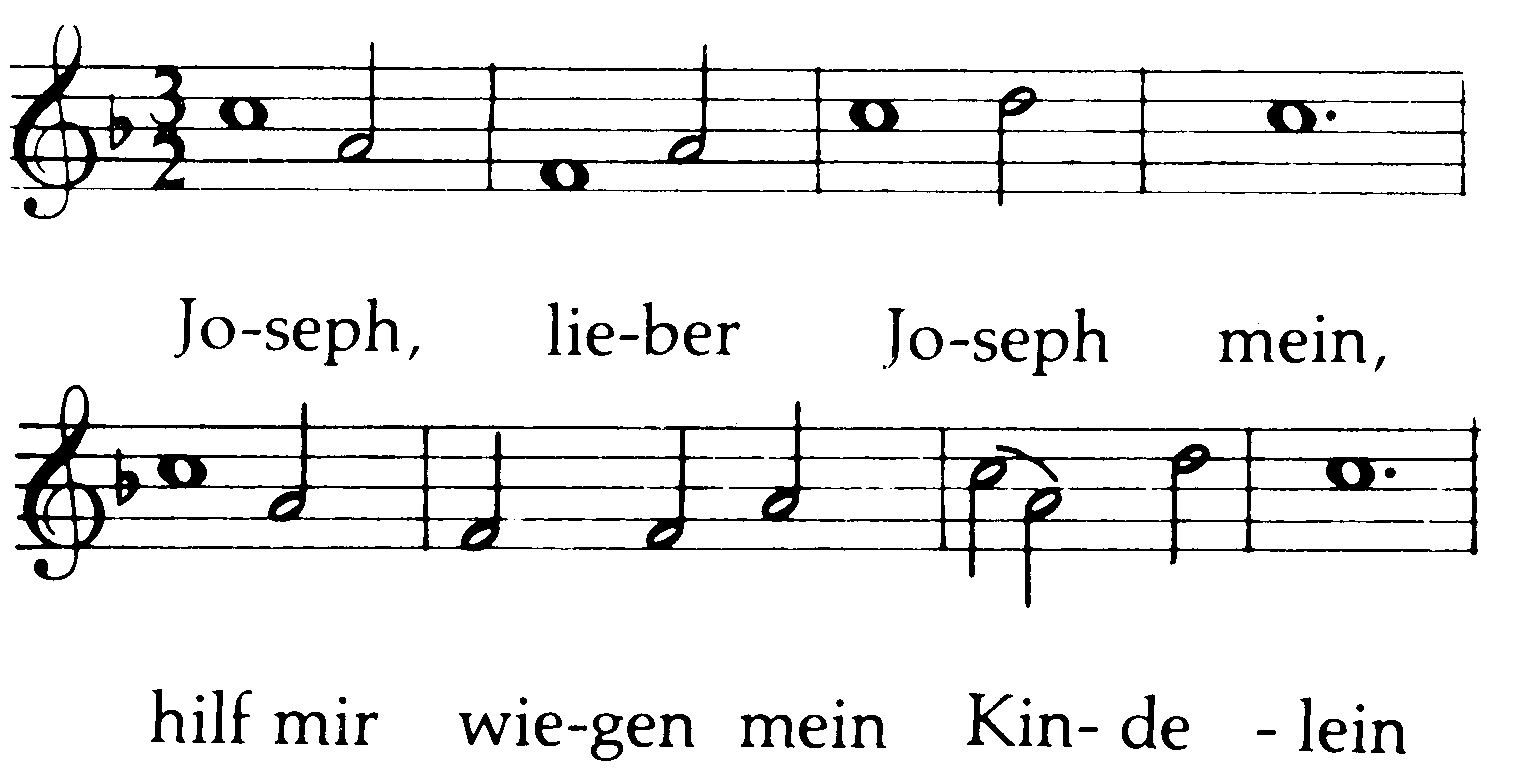

For a minuet, there is a G major piece in which, over a rustic drone, is heard the melody of the popular German Christmas carol, “Joseph, lieber Joseph mein” (also known to Latin words: “Resonet in laudibus”). The melody is presented in a particular version – not the one usually found in hymn books, but one known to every denizen of Salzburg because it was played in the appropriate season by a mechanical carillon in the tower of the Hohensalzburg Castle that dominates the city. (There also exists an eighteenth-century Salzburg arrangement for wind band of this version of the carol, and Leopold Mozart himself published an arrangement of it for harpsichord. Wolfgang returned to it in 1772, quoting it in the original slow movement of his symphony, K. 132.) This movement was suppressed in the Donaueschingen manuscript. The contrasting D major trio takes the form of an attractive horn duet with merely a bass-line accompaniment.

The 2/4 allegro finale offers us another bright noise, to close as we began. It is a tiny, two-part movement, with lively, al fresco horn duets at the beginning of the second section.

The Italian Symphonies

Mozart’s youth in Salzburg was punctuated by three journeys to Italy, which lasted from 13 December 1769 to 28 March 1771, 13 August 1771 to 15 December 1771, and 24 October 1772 to 13 March 1773. Thus during the period from just before Mozart’s fourteenth birthday until shortly after his seventeenth, he spent a total of about twenty-two months in the land that many of his contemporaries considered the fount of modern music. In so doing, Mozart and his father were following a well-beaten path, for generations of German composers had served apprenticeships in Italy, including Handel, J. C. Bach, Hasse and Gluck. The primary goal of such journeys was usually mastery of Italian opera, but training in other musical genres was not neglected. This was the situation discussed in an essay of 1770 by Nicolas Etienne Framery entitled “Some Reflexions upon Modern Music”, from which the following fragments are taken:

“While the French and the Italians were disputing which of them possessed music, the Germans learned it, going to Italy for that purpose ... The German artists filled the public conservatories of Naples ... They had all the raw materials required of great musicians; they lacked only the discipline to organise those materials, and they had no trouble acquiring that ... Upon leaving the schools, the Italian pupils remain in their own country ... The Germans, on the contrary, return to their country. They have carefully preserved their prodigious accumulation of [musical] science. They have tested the very fortunate use of wind instruments of which their nation makes much use, and they have known how to draw the most from them … They have realised that all expression does not suit vocal melody; that there are a thousand nuances which the orchestra is much more fit to render [than the voice]. They have tried, they have succeeded, and have raised themselves far above their masters, who now rush to imitate them ...”

From the letters that Mozart and his father wrote home during these travels (for Mozart’s mother and sister remained in Salzburg), we learn that they had need of symphonies for public and private music-making, that they brought some symphonies with them from Salzburg, and that Wolfgang composed others while in Italy.

The first such concert – which took place in Verona on Friday, 5 January 1770, in the Teatrino della Accademia Filarmonica – was probably typical of many of them. Leopold described the occasion in a letter to his wife:

“In all my life I have never seen anything more beautiful of its kind. ... It is not a theatre, but a hall built with boxes like an opera house. Where the stage ought to be, there is a raised platform for the orchestra and behind the orchestra another gallery built with boxes for the audience. The crowds, the general shouting, clapping, noisy enthusiasm and cries of ‘Bravo!’ and, in a word, the admiration displayed by the listeners. I cannot adequately describe to you.”

A newspaper account confirms the enthusiasm with which Wolfgang was received, mentioning “a most beautiful introductory symphony of his own composition, which deserved all its applause”. A similar programme given in Mantua at the Teatro Scientifico on 16 January 1770, to acclaim equal to that received in Verona, demonstrates the characteristic function usually assigned symphonies in concerts of the second half of the 18th-century, that of “framing” the event:

1. First and second movements of a symphony by Mozart

2. Harpsichord concerto played at sight by Mozart

3. Aria sung by the tenor Uttini

4. Harpsichord sonata played at sight and ornamented by Mozart, and then repeated in a different key

5. Violin concerto by a local virtuoso

6. Aria improvised by Mozart upon a poem handed him on the spot, sung by him to his own harpsichord accompaniment

7. Two-movement harpsichord sonata improvised by Mozart on two themes given him on the spot by the concertmaster; at the end the two themes were “elegantly” combined

8. Aria sung by the soprano Angiola Galliani

9. Oboe concerto by a local virtuoso

10. Harpsichord fugue improvised by Mozart on a theme given him on the spot

11. Symphony accompanied by Mozart on the harpsichord from a first violin part given him on the spot

12. Duet by two professional musicians

13. Trio “by a famous composer” in which Mozart performed at sight the first violin part, ornamenting it

14. Finale of the opening symphony.

As for his fellow musicians in Mantua, Wolfgang wrote in a letter, “The orchestra was not bad”. The only drawback to these otherwise brilliant events was explained by Leopold to his wife:

“... neither this concert in Mantua nor the one in Verona were given for money, for everybody goes in free; in Verona this privilege belongs only to the nobles who alone keep up these concerts; but in Mantua the nobles, the military class and the eminent citizens may all attend them, as they are subsidised by Her Majesty the Empress. You will easily understand that we shall not become rich in Italy ...”

The symphonies played at Verona and Mantua must have been brought from Salzburg. The first hint of symphonies composed in Italy is found in Wolfgang’s letter of 25 April 1770, written from Rome to his sister: “When I have finished this letter I shall finish a symphony which I have begun ... A symphony is being copied (father is the copyist, for we do not wish to give it out to be copied, as it would be stolen).” On 4 August, writing from Bologna in another letter to his sister, Mozart remarked, “In the meantime I have composed 4 Italian symphonies ...” This expression “Italian symphonies” has usually been taken to mean three-movement symphonies, that is to say, symphonies without the minuet and trio characteristic of the so-called Viennese symphony of the period. Hence it has frequently been asserted, concerning those of Mozart’s symphonies thought to originate in Italy which do have minuets, that the latter must have been added later for use in Salzburg. But Mozart wrote to his sister of his desire to introduce to Italy minuets in the German manner because, according to him, Italian minuets “last nearly as long as an entire symphony” and “have many notes, a slow tempo, and are many bars long”. By “Italian symphonies”, therefore, Mozart may simply have meant symphonies written in and for Italy, without reference to the presence or absence of minuets.

Two symphonies (K. 73l/81 and 73q/84) exist in sets of non-autograph parts in Vienna with indications of their provenance. The parts for the former symphony are labelled in Roma 25. April 1770. The parts for the latter bear the inscription at the top In Milano, il Carnovale 1770, but at the bottom this is contradicted by another inscription: Del Sig[no]re Cavaliero Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart à Bologna, nel mese di Luglio 1770. Nevertheless, the two symphonies written in Rome in April are probably K. 73l/81 and 73q/84, and the four symphonies mentioned in Bologna in August most likely include those two works plus others, the identity of which is unclear.

For five other symphonies which may date from Mozart’s Italian journeys, neither autographs nor other “authentic” sources survive (K. 73m/97, 73n/95, 74g/Anh. C11.03/Anh. 216, 75 and 111b/96.) These have been given their chronological positions in the Köchel Catalogue on imprecise stylistic grounds and, in fact, cannot even be proven to be by Mozart. Problems of attribution are severe among the symphonies of this period. Four symphonies have attributions to both Leopold and Wolfgang in various sources (K. 73l/81, 73m/97, 73n/95, and 73q/84), and the last of these is attributed also to Dittersdorf.

Of Mozart’s eleven Italian symphonies, eight are in D major. A clue as to why this is so may be contained in a cryptic remark Mozart made to his father in 1782 about his Haffner symphony: “I have composed my symphony in D major, because you prefer that key.” This may be because D major is simultaneously a brilliant yet easy key for string players, which, unlike the other “easy” keys (G and A major) is also one of the trumpet keys, permitting the addition of those instruments whenever they were available. It remains only to add that Mozart’s D major symphonies of the 1770s seem more conventional and less personal in character than several of those he wrote in other keys.

The most famous Italian orchestras in the early 1770s were those of the opera houses of Turin, Milan and Naples. We have pictures of the Turin orchestra in performance, as well as seating diagrams of the Turin and Naples orchestras. The players sat facing one another in long rows, half toward the audience and half toward the stage. Leopold wrote in December 1770 that the Milan orchestra consisted of 28 violins, 6 violas, 2 cellos, 6 double basses, 2 flutes who doubled on oboe, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, kettledrums, and 2 harpsichords. How such orchestras rearranged themselves when performing concerts rather than operas was described by Galeazzi (1791):

“The best placement for good effect is to arrange the players in the middle of the hall with the audience all around them; but the visual impression is more satisfying if you arrange them to one side, against one of the walls of the drawing-room (supposing a rectangular-shaped area), because the audience thus enjoys the entire orchestra from the front. The violins are then placed in two rows, one opposite the other so that the firsts are looking at the seconds ... With regard to the bass-line instruments, if there are only two, place them near the harpsichord (if there is one) in such a way that the violoncello remains near the leader of the first violins and the double bass on the opposite side, and between them the maestro or harpsichordist; but if there are more bass-line instruments, and if they are played by good professional musicians, place them at the foot – that is, at the other extremity – of the orchestra, otherwise you should place them as near to the firsts as you possibly can. The violas are always best near the second violins, with whom they must often unite in thirds, in sixths, etc., and the oboes are best alongside the firsts. The brass can then be placed not far from the leader. In this disposition all the heads of sections – namely, the leader, the principal second violin, the principal cello, the maestro, the singers, etc. – are neighbours, by which means perfect ensemble cannot but result.”

For smaller orchestras, a semi-circular arrangement of the players was also employed. A passe-partout title page used by the Florentine publisher Giovanni Chiari in the 1780s shows this particular orchestral layout (see illustration). The orchestra is rehearsing either on a stage with sets representing a formal garden, or in an actual garden with topiary trees. On the left, from front to back, we see 2 horns, 4 first violins, the first oboe, and the first viola; on the right 2 trumpets (showing plainly why Mozart designated them “trombe lunghe” in his scores), 4 second violins, the second oboe, and the second viola. In the centre at the back we see the maestro al cembalo, surrounded by a cello, a double bass and a singer of each sex. Another man seems to be directing the rehearsal, while fashionably attired ladies and gentlemen stroll, chat or listen, a dog barks and someone sweeps up.

For these performances we have applied Galeazzi’s instructions to the personnel lists of Turin, Milan and Naples for the large-scale symphonies (those with trumpets and kettledrums), and followed the Chiari engraving for the small-scale ones (those without these festive instruments). The large-scale orchestra has the strings at 12-12-4-2-6, five bassoons (reinforcing the bass line), the necessary wind, and two harpsichords improvising a continuo. The great strength of the violins and double basses and the relative weakness of the violas and cellos creates a sound quite distinct from that of the London, Paris, Salzburg, or Vienna orchestras, also recreated in this series of recordings. The predominance of the double basses over the cellos creates an organ-like sonority that makes the acoustic of a theatre or hall resemble that of a cathedral. The timbre is more “archaic”, that is, it tends toward the Baroque ideal and away from the Classical. The strong contingent of bassoons compensates for the small number of cellos and etches the details of the bass line with scintillating clarity.

For the small scale orchestra, the strings are 6-5-2-2-1 (following further advice from Galeazzi about proper string balance), with one bassoon, the necessary wind and one harpsichord. The layout in the Chiari engraving emphasises a special feature of the orchestration of Mozart’s Italian symphonies: the first oboe often doubles the violin in unison or the first viola in octaves, while, in a similar fashion, the second oboe often doubles the second violin or the second viola.

Symphony in D major, K. 73l [K. 81]

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegro molto

As we have, seen, a manuscript copy of this work dated Rome, 25 April 1770 attributes it to Wolfgang, but in a Breitkopf thematic catalogue published in 1775 it is listed as a work of Leopold’s. The symphony – bright, superficial and conventional – has generally been accepted, however, as being by Wolfgang. The orchestra is small: pairs of oboes and horns, strings, and harpsichord continuo.

The first movement opens with a rising D major arpeggio, an idea that is turned upside down for the opening of the finale. It continues as a compactly organised sonata form without repeats, and with a literal recapitulation. The tiny “development” section of twelve bars could perhaps more aptly be called a transition.

The second movement, a G major andante in 2/4, features a dialogue between the first and second violins, the conversation soon broadening to include the pair of oboes. In this serene binary movement with both halves repeated Wyzewa and Saint-Foix detected the influence of the Milanese composer Giovanni Battista Sammertini.

The 3/8 finale, marked allegro molto, is the sort of movement known as a “chasse” or “caccia” – that is, a jig filled with hunting-horn calls. This “hunt” would seem to be one contemplated from the comfort of the drawing room, however, far from the mud and commotion of the actual event. The form is a binary arrangement as described for the first movement of K. 19a.

Symphony in D major, K. 73m [K. 97]

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Presto

This work survives in a single undated, non-autograph manuscript in the archive of Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. Its provenance is therefore completely unknown. In recent editions of the Köchel catalogue it has been assigned to Rome, April 1770, on largely illogical grounds. It has nonetheless been included here among Mozart’s Italian symphonies, for lack of a better hypothesis.

The first movement is an Italian overture in style and spirit, in sonata form with no repeated sections. The trumpets add to the festivity, as well as helping to outline the movement’s structure. A neatly worked-out, brief development section travels through G major, E minor and B minor, before re-establishing the home key.

The andante, a binary movement in G major 2/4, with both halves repeated, exhibits an attractive mock-naïveté. The minuet that follows adheres to Mozart’s preference (documented above) for brevity. In fact, the spirit of the movement is more of the ballroom than the symphony. The G major trio omits the wind and, by its chamber-music character, provides an excellent foil to the pomp of the minuet proper.

The finale is a gem. It is a jig-like movement (presto, 3/8) in sonata form, with a brief but effective development section. Furthermore, the movement contains an uncanny adumbration of a passage in the first movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, not only in the theme itself but in the way in which it is immediately repeated with a turn to the minor. Beethoven cannot have known this work, so we can only speculate about coincidence or an as-yet-undiscovered common model.

Symphony in D major, K. 73n [K. 95]

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Presto

The source for this work is identical to that of the previous one, and doubts about its provenance are equally severe. It has been given the same place and date as the previous symphony on similarly unsatisfactory grounds, and is included here for the same reason.

The first allegro, alla breve, opens with an idea more or less the same as that which launches the symphonies K. 73m/97 and 74. It is in sonata form without repeats. The movement is an essay in orchestral “noises” put together to form a coherent whole. That is, there are no memorable, cantabile melodies, but rather a succession of idiomatic instrumental devices, including repeated notes, scales, fanfares, turns, arpeggios, sudden dynamic changes, and so on. Descriptions and explanations of musical form tend to fall back on linguistic analogies. In this case, however, such an analogy would lead us into the absurd position of having to imagine meaningful prose composed of articles, conjunctions and prepositions! Responding to this paradox, Schultz refers to such movements as “purely decorative”. Leopold Mozart once called a symphony of J. Stamitz in this vein “nothing but noise”. The eighteenth-century aesthetician Lacépède thought that, therefore, symphony movements needed programmes to make sense of otherwise “meaningless” musical events. These reactions, and the failure of the linguistic analogy, point to a weakness of aesthetic theory in dealing with an art of abstract sounds unsupported by association with concrete verbal ideas. (A parallel may be drawn with the difficulties surrounding the acceptance of non-representational painting in the twentieth century.)

The first movement comes to a halt on a D major chord with an added seventh, leading directly into the G major 3/4 andante. Whatever lyricism may have been lacking in the previous movement is more than atoned for in its songful successor. The trumpets and kettledrums drop out and the oboes are replaced by flutes, which lend a pensive, pastoral hue to this sweet-sounding interlude.

The oboes and trumpets return for the boisterous minuet, in which Mozart presents yet another example of concision for the instruction of his longer-winded Italian colleagues. The trio in D minor omits the trumpets, and with its quiet intimacy nicely sets off the return of the minuet. The allegro 2/4 finale returns us to the sonata form and happy noises of the opening movement. The two movements are even linked by the same opening gesture.

Symphony No. 11 in D major, K. 73q [K. 84]

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegro

This symphony survives in manuscripts in Vienna (attributed to Wolfgang), Berlin (attributed to Leopold), and Prague (attributed to Dittersdorf). A close stylistic analysis of the work by LaRue has shown that Wolfgang is the most likely of the three to have been the composer. As has already been mentioned, the Vienna manuscript bears two inscriptions: In Milani, il Carnovale 1770 and Del Sig[no]re Cavaliero Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart à Bologna, nel mese di Luglio 1770. These apparently contradictory bits of information may perhaps be resolved in the following manner: in 1770 Carnival lasted from 6 January until 27 February, and the Mozarts were in Milan from 23 January to 15 March, and in Bologna from 20 July to 13 October. Hence, if the inscriptions are to be trusted, this symphony may well have been drafted in Milan in January or February and have received its final revision in Bologna in July.

The opening allegro in common time exhibit a fully-fledged sonata form without repeated sections. There are, well differentiated, an opening group of ideas, a second group and a closing group, a brief development section of eleven bars, and a full recapitulation.

The 3/8 andante in A major has a Gluck-like ambience. It is also in sonata form but without a development section. The finale, allegro 2/4, opens with a fanfare borrowed from the first movement. This idea is withheld during the rest of the exposition, development and recapitulation, to serve as coda. Most of the movement, the fanfare aside, is filled with a constant flow of triplets, which tum it into a kind of jig. One passage in particular reminds us of Figaro’s prattling in Rossini’s Barber of Seville.

Symphony No. 10 in G major, K. 74

1. Allegro – andante

2. Rondo

The autograph of this symphony is among those formerly in Berlin and now at Kraków. It bears neither date nor title, although at the end of the last movement Mozart expressed his gratitude (or perhaps relief) at its completion by writing “Finis Laus Deo”.

This work is written in Italian overture style, that is, the boisterous first movement is in sonata form without repeats, and flows into the finely-wrought second movement without a halt – in this case, without even a new tempo indication or double barline. At this juncture the quavers in the oboes continue unperturbed as the metre shifts from common time to 3/8 and the key from G major to C major.

The finale is marked simply Rondeau, and the French spelling gives a hint of the character of its refrain, which is that of a French contredanse. Especially noteworthy in this movement is the “exotic” episode in G minor, which is perhaps the earliest manifestation of Mozart’s interest in “Turkish” music – an interest exhibited in portions of such pieces as the ballet music for Lucio Silla, K. 135, the violin concerto, K. 219, the piano sonata, K. 300i/331, The Abduction from the Seraglio, K. 384, and the aria, “Ich möchte wohl der Kaiser sein”, K. 539. These pieces have nothing to do with true Turkish music, but represent rather a style found occasionally in the music of Michael and Joseph Haydn, Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart, Dittersdorf, Gluck, and other middle European composers of the period. The origins of this style are as follows: “exotic” elements were drawn from the indigenous music of the region bordering the Ottoman Empire, where the Hungarian peasants and gypsies imitated or parodied the music of their Moslem neighbours. The “exotic” elements often included a leaping melody, a static bass with reiterated notes, occasional chromatic touches in the melody, a minor key, profuse ornamentation in the form of grace notes, trills and turns, and a marchlike tempo in 2/4 time. In parts of Hungary the peasants referred to this style of music as “Törökos”, which means precisely the same as Mozart’s “alla turca”, that is, “in the Turkish mariner”.

Symphony in D major, K. 74a [K. 87]

1. Allegro

2. Andante grazioso

3. Presto

This work originated as the overture for Mozart’s opera, Mitridate, re di Ponto. The opera was begun in September 1770. Wolfgang composed the recitatives first, then turned to the arias, and probably wrote the overture last. The opera had its first general rehearsal on 17 December and its première on 26 December, to general approbation. Wolfgang presided over the first three performances at the harpsichord, as was then the custom and required by his contract. The overture circulated widely in the eighteenth century as a concert symphony.

The autograph of the opera is lost, and only sketches of a few numbers survive in Mozart’s hand. In the extant sources for the opera, the orchestra employed in the overture calls for pairs of flutes, oboes and horns, and strings. Examination of the rest of the opera reveals, however, that the orchestra also includes pairs of trumpets and bassoons – instruments that would hardly have been silent during the festive overture. (Leopold Mozart, it will be recalled, reported the presence of trumpets and bassoons in the Milan orchestra.) Due to these circumstances, we have followed a set of eighteenth century manuscript parts in Donaueschingen for the overture. These provide for bassoons throughout, doubling the bass line, and trumpets in the first and last movements. Originally there must have been a part for kettledrums, but as that has been lost, we have had to improvise one.

The libretto of Mitridate, re di Ponto was the work of Vittorio Amedeo Cigna-Santi, based on Racine’s Mithridate. A brief synopsis of its plot may serve to indicate the atmosphere that Mozart attempted to evoke in writing this symphony.

Mithridates VI Eupator (111-63 B.C.) had conquered Cappadocia and other provinces beyond the Bosphorus as far as the Crimea. In the third Mithridatian War, however, he was defeated by the Romans under Sulla and Pompey and fled to his kingdom of Pontus by the Bosphorus where, believing himself to have been betrayed by his sons and wife, he killed himself by falling on his sword, leaving open the way for a happy ending of the opera – at least for the other characters!

Symphony in D major, K. 111, 111a [K. 120]

1. Allegro assai

2. Andante grazioso

3. Presto

This symphony also began its life as an overture, in this case to the “theatrical serenade” Ascanio in Alba, K. 111. Ascanio was written for the celebrations surrounding the wedding of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand and the Princess Maria Ricciarda Beatrice of Modena. Mozart began to compose it at the end of August, 1771, and the work was completed by 23 September. Its first performance in Milan on 17 October was a success, apparently eclipsing a new opera by Hasse that was also part of the festivities. That the great choreographer Noverre created the ballets to Ascanio undoubtedly added to its éclat.

In this instance Wolfgang went against his usual custom and composed the overture first. The reason for this was probably that he had decided to integrate the end of his overture into the beginning of the serenade. Thus, following the allegro movement, the andante served as a ballet, to be danced by “the Graces”. The libretto explains the setting portrayed by Mozart’s andante:

“A spacious area, intended for a solemn pastoral setting, bordered by a circle of very tall and leafy oaks which, gracefully distributed all around, cast a very cool and holy shade. Between the trees are grassy mounds formed by Nature but adapted by human skills to provide seats where the shepherds can sit with graceful informality. In the middle is a rustic altar on which may be seen a relief depicting the fabulous beast [the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus?] from whom, according to legend, the City of Alba derived its name. A delicious, smiling countryside – dotted with cottages and encircled with pleasant, not too distant hills from which issue abundant and limpid streams – is visible through the spaces between the trees. The horizon is bounded by very blue mountains, which merge into a most pure and serene sky.”

For a finale, the overture had an allegro 3/4 movement with choruses of Spirits and Graces singing and dancing, thus anticipating (in a modest way) Beethoven’s innovation in his Ninth Symphony. When Mozart decided, at an unknown date, to turn the overture into a concert symphony, he kept the first two movements and replaced the choral movement with a brief, extrovert giga in the form A-B-A-Coda. The autographs of both Ascanio and the new finale are in the West Berlin Library.

Symphony in C major, K. 111b [K. 96]

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Allegro molto

Here we have another rootless symphony. Its assignment in the Köchel catalogue to Milan at the end of October or beginning of November 1771 is largely arbitrary, as the editors of the most recent edition of that venerable catalogue admit.

With a bright tantivy, of a sort that opens many an eighteenth-century orchestral work, the first movement is off and running. And run it does, with tremolo and scales, through a concise ternary form to a rather predictable conclusion.

The andante in C minor, 6/8, is a siciliano in an archaic style that recalls such late-Baroque works as the Pastoral Symphony and “How beautiful are the feet” in Handel’s Messiah, and certain movements in violin sonatas of Locatelli, Tartini, Nardini and Vivaldi. This is an exceptionally profound slow movement for a symphony of c 1771 (if indeed that is its date), but the stylistic disparity between its neo-Baroque intensity and the conventional modernity of the movements surrounding it is difficult to explain.

The minuet and trio and the finale return to the galant extroversion of the first movement. The finale, fashioned from a kind of quick step, rounds off the work with infectious exuberance.

Symphony No. 13 in F major, K. 112

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Allegro molto

The autograph of this work is in New York, owned by the Heinemann Foundation. It is a clearly-written fair copy inscribed Sinfonia del Sig[no]re Cavaliere Amadeo Wolfgango Mozart à Milano 2 di Novemb. 1771 (the first word in Wolfgang’s hand, the remainder in Leopold’s). It may have had its first performance at an orchestral concert that Leopold and Wolfgang gave on 22 or 23 November at the residence of Albert Michael von Mayr, who was keeper of the privy purse to Archduke Ferdinand, son of Empress Maria Theresa and Governor of Lombardy.

That this was conceived as a concert piece and not an overture can be seen in the first, second and fourth movements, in which all sections but the coda of the finale are repeated. From the beautifully proportioned sonata form of the first movement, through the careful part-writing of the andante (for strings alone) to the energetic giga rondo-finale, a spirit of confidence and solid workmanship seems to emanate from this symphony, fruits perhaps garnered from the success of Ascanio the previous month.

The minuet shows sign of other origins, however. In this movement the violas double the bass line, instead of having an independent part to play, as is customary in Mozart’s symphonic minuets. Because Mozart’s ball-room minuets and contredanses were customarily composed without viola parts, this unusual feature of the minuet of K. 112 may mean that it fulfilled another function before being pressed into service in this symphony. The trio (for strings alone) may be new, however, as there the violas do carry an independent voice.

Mozart and the symphonic traditions of his time

Salzburg and its Orchestra

In the year 1757 there appeared in a Berlin music magazine an anonymous “Report on the Present State of the Musical Establishment at the Court of His Serene Highness the Archbishop of Salzburg”. This report lists by name and function those serving the archbishop in musical capacities, with biographies of the more important personages and brief notes on others who had attained special distinction. It begins with the Kapellmeister Johann Ernst Eberlin (1702-62), the Vice-Kapellmeister Giuseppe Francesco Lolli (1701-78), and the three court composers: Caspar Cristelli (dates unknown), Leopold Mozart (1719-87) and Ferdinand Siedl (dates unknown). Concerning Leopold Mozart we read:

“Herr Leopold Mozart from the Imperial City of Augsburg. First violinist and leader of the orchestra. He composes both church and chamber music. He was born on the 14th of November, 1719, and soon after completing his studies in philosophy and law entered the princely service in the year 1743. He has made himself known in every branch of composition, without, however, issuing anything in print except for 6 Sonatas à 3 that he himself engraved in the year 1740 (principally in order to gain experience in the art of engraving). In July 1756 he published his Violinschule.

Among the compositions by Herr Mozart which have become known in manuscript, numerous contrapuntal and church pieces are especially noteworthy; moreover a large number of symphonies, some only à 4, but some with all the generally current instruments; likewise more than thirty grand serenades, in which are introduced solos for various instruments. Apart from these he has composed many concertos, especially for transverse flute, oboe, bassoon, horn, trumpet, etc., countless trios and divertimentos for divers instruments; also twelve oratorios and a host of theatre pieces, even mime plays. and especially music for certain special occasions, such as a military piece with trumpets, kettledrums, side drums and fifes, together with the ordinary instruments; a Turkish piece; a piece with a steel xylophone; and music for a sleigh-ride with five sleigh-bells; not to mention marches, so-called notturnos, many hundreds of minuets, opera dances and suchlike smaller pieces ...

The three court composers play their instruments in the church as well as in the chamber, and, in rotation with the Kapellmeister, have each the direction of the Court Music for a week at a time. All the musical arrangements depend solely upon whoever is in charge each week, as he, at his pleasure, can perform his own or other persons’ pieces.”

This report was in fact written by Leopold, who gives himself away by immodestly making his own biography more than twice as long as (and more personal than) any of the others. His anonymity permitted him this self-indulgence, as well as the possibility of criticising one of his violinist colleagues for preferring to play technically difficult pieces while possessing a weak tone. At the time of this report, Leopold’s prospects must have seemed bright indeed: he was well thought of at the Salzburg Court and could reasonably hope for eventual promotion to Kapellmeister. His Violin Method was already receiving favourable critical notice. His devoted wife, after three tragic infant deaths, had presented him with two healthy children, Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia (“Nannerl”), soon to turn six, and Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus, just turned one. But Leopold’s old age was to be a bitter one: for his wife died on a futile journey to find a post for Wolfgang, his son never achieved a suitable post and married (in Leopold’s eyes) beneath his station, and he himself never advanced beyond the rank of Vice-Kapellmeister, a fate that he brought down on his own head by virtually abandoning his own career in order to promote that of his extraordinary son.

Like Leopold’s hopes, the Salzburg orchestra steadily declined, not so much in size as in discipline and morale. By the late 1770s, sloppy playing, slovenly dress, absenteeism and drunkenness had become frequent problems. At the beginning of Wolfgang’s musical consciousness, however, the Salzburg orchestra was well run and indeed large for its time. Counting apprentices and choir boys, Leopold’s report chronicled some 46 instrumentalists and 56 singers, leaving aside an organ builder, a string-instrument maker, three organ blowers, and five vacant positions. At first examination the string section would appear to have consisted of only 16 players (5-5-2-2-2). This is deceptive, however, because many of the woodwind players also played string instruments and, as Leopold added at the end of his report. “There is not a trumpeter or kettledrummer in the princely service who does not play the violin well, who then all appear when large-scale music is performed at Court and play second violin or viola, which it is in the purview of whoever is in charge of the weekly direction to order.” The court musicians were also often supplemented by various amateur performers. Thus a string section of 10-10-4-6-3 or larger could be assembled without great difficulty. For the ordinary daily rounds of music-making, however, a system of rotation provided the necessary players without everyone having to play on any given day.

We have reconstituted the orchestra for these recordings as it may have been heard at festive occasions during the year: the strings 9-8-4-3-2, and the necessary woodwind, brass, kettledrums and harpsichord, with three bassoons doubling the bass line whenever obbligato parts for them are lacking.

The Symphonies of 1766-72

The eleven symphonies presented here, written between the ages of 10 years 2 months and 16 years 4 months, may be divided into four categories: three overtures intended in the first instance for vocal works but later used as independent concert pieces (K. 35, 38, 74c); five Germanic concert symphonies with minuets and (usually but not always) with repeated sections in all movements, (K. 73, 75, 75b, 114, 124); two Italianate overture-symphonies, without minuets, (K. 128, 129); and one five-movement symphony drawn from an eight-movement serenade (K. 62a). None of these works were published in the 18th century.

Chronologically the production of these works falls into four periods of residence in Salzburg, in between those trips on which Leopold took Wolfgang both to educate him and to exploit his status as child prodigy. This may be represented as follows:

Journey to Mannheim – Paris – London – The Hague

Stay in Salzburg, 29 or 30 November 1766-11 September 1767: K. 35, 38

Journey to Vienna

Stay in Salzburg, 5 January 1769-13 December 1769: K. 62a, 73

Journey to Italy

Stay in Salzburg, 28 March 1771-13 August 1771: K. 74c, 75, 75b

Journey to Italy

Stay in Salzburg, 15 December 1771-24 October 1772: K. 114, 124, 128, 129 [as well as K. 130, 132, 133, 134]

Journey to Italy.

Added to the third of these four Salzburg stays should perhaps also be the Symphony in B flat, K. Anh. C11.03 [K. Anh. 216/74g].

Furthermore, three lost symphonies known only by their incipits (K. 66c [K. Anh. 215], 66d [Anh. 217], 66e [Anh. 218]) may belong to the second or third of these periods.

In February 1772, Leopold Mozart wrote to the Leipzig publisher Breitkopf offering him various of his son’s works, including symphonies. It is usually stated that, as far as symphonies are concerned, nothing came of Leopold’s offer, because the Leipzig publisher never printed any of Wolfgang’s symphonies during the composer’s lifetime. This constitutes a serious misunderstanding. Breitkopf printed music only by means of moveable type, a method suited primarily to keyboard music, songs, and other items in short score. For the “publication” of sets of parts, the customary methods were either engraving or hand copying, and in fact the bulk of Breitkopf’s business consisted of manuscript copies. This therefore must have been what Leopold had in mind, and in the old Breitkopf archives there was indeed found a collection of parts for ten of Wolfgang’s symphonies from the period 1767-73.

Some six years later Leopold wrote to Wolfgang, rather unfairly and in the light of his own dealings with Breitkopf, I think, hypocritically:

“It is better that whatever does you no honour, should not be given to the public. That is the reason why I have not given any of your symphonies to be copied, because I suspect that when you are older and have more insight, you will be glad that no one has got hold of them, though at the time you composed them you were quite pleased with them. One gradually becomes more and more fastidious.”

Symphony in C major, K. 35

Sinfonia: Allegro

In late 1766 and early 1767 Mozart set Part 1 of a Lenten oratorio, Die Schuldigkeit des ersten und fürnenmsten Gebots (“The Obligation of the First and Foremost Commandment”). The second and third parts of this oratorio – the text of which is by the Salzburg Burgomaster Ignaz Anton Weiser (1701-85) – were set by Michael Haydn and Anton Adlgasser respectively. Mozart’s portion received its première in the Knights’ Hall of the archi episcopal palace on 12 March, with a second performance on 2 April. Haydn’s portion was performed on 19 March, and Adlgasser’s probably on 26 March. According to the libretto for Part 1, “The action takes place in a pleasant landscape with a garden and a small wood”, and there are stage directions throughout. Nonetheless, it is likely that the “theatre of the mind” was intended rather than the stage. The protagonists of this frigid allegory are: The Spirit of Christianity, The World Spirit, Divine Mercy, and Divine Justice. In Part 2 “A Lukewarm and Afterwards Ardent Christian” is added to the cast of characters. Mozart’s setting consists of seven arias and a concluding terzetto, interspersed with recitatives. This is prefaced by an orchestral movement headed Sinfonia. Allegro, which is the symphony presented here.

From its character this energetic common-time allegro, with its Italianate opening melody in sixths accompanied by a repeated-note bass line, could just as well have served to launch an opera. Carl Ferdinand Pohl, who in 1864 rediscovered the lost autograph manuscript of Die Schuldigkeit in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle (where it is still located), characterised the “Sinfonia” as “simple and natural in structure”. It is in binary form, with both halves repeated. The opening section rapidly comes to rest on the dominant, and a contrasting “sigh” motive is heard several times. (This motive is featured prominently in the second half of the movement, in thirds, sixths, and octaves; upside down and rightside up.) A brief return of the opening idea leads to a sonorous closing section, with tremolo in the violins and the melodic interest transferred to the bass. The second half begins as did the first but in the dominant key. No new ideas are introduced; rather the ideas of the first half are skillfully manipulated through several keys and changes of orchestration, before the return of the home key and the opening idea a mere fifteen bars from the end. The entire small-scale movement is well wrought and in the period’s most modern, galant vein.

Symphony in D major, K. 38

Intrada: Allegro

In Leopold Mozart’s catalogue of his son’s childhood works, one reads the entry: “Apollo and Hyacinth, music to a Latin comedy for Salzburg University, with five singing personae. The original score had 162 pages. Written in [Wolfgang’s] eleventh year 1767.” Salzburg University was run by the Benedictines, who, in their schools, had long had the custom of mounting plays, operas and even ballets on morally edifying themes. In this instance, a spoken tragedy was being staged, and Mozart’s “opera” was, in the 18th-century manner, divided into three portions, which were used as a prologue and as intermezzos between the acts of the tragedy.

Apollo and Hyacinth was performed by students and teachers in the Great Hall of the University on 13 May. Although it seems to have been well received, there is no record of further performances. The libretto, in Latin and in the style of the Italian opera librettos of the day, relates the story found in Ovid and elsewhere of Apollo’s accidental slaying of the youth Hyacinth, whose blood was transformed into the flower that bears his name. The work’s overture, or Intrada as Mozart labelled it, is listed as an independent “Sinfonia” in an early 19th-century Breitkopf & Härtel manuscript catalogue.

The single-movement work, in 3/4 and marked allegro, is even briefer than the previous symphony. Like that work this too is in binary form, but with only the first half repeated. Saint-Foix remarks upon the work’s “symphonic” character. This may refer to the near total absence of cantabile melody in this “Sinfonia”, with its scales, arpeggios, syncopations, repeated notes and fanfares. All in all, a happy noise for a festive occasion.

Apollo and Hyacinth has one further symphonic connection: a duet from it (No. 8, “Natus cadit”) was itself transformed by Mozart into the slow movement of the Symphony in F major, K. 43.

Symphony in D major, K. 62a [K. 100]

1. Serenata: Allegro

2. Menuetto & Trio

3. Andante

4. Menuetto & Trio

5. Allegro

This symphony was extracted from an orchestral serenade – a logical procedure given that the occasions for serenades and for symphonies were quite different, and that serenades were made up of interlarded symphony and concerto movements prefaced by a march. In the present case the interpenetration of the constituent genres is as follows:

1. Marche: Maestoso [K. 62]

2. Allegro: Serenata

3. Andante

4. Menuetto

5. Allegro

6. Menuetto

7. Andante

8. Menuetto

9. Allegro

Symphonic movements: 2 Allegro; 6 Menuetto; 7 Andante; 8 Menuetto; 9 Allegro

Movements of a sinfonia concetante for oboe and horn: 3 Andante; 4 Menuetto; 5 Allegro

The undated autograph manuscript of the serenade is found among an important group of manuscripts that was in Berlin until World War II and is now in Kraków. The work is lacking in Leopold’s 1768 catalogue of his son’s works and mentioned by Wolfgang himself in a letter of August 1770, so these two documents provide us with termini a quo and ad quem. The large scale of the piece and the presence of trumpets and kettledrums suggest that it was intended for a celebration at court, and not (as is usually stated) as a “Finalmusik” for the end of the summer term at Salzburg University.

This is one of five Mozart serenades that exist in symphony versions. For three of the five there are extant sets of orchestral parts of the symphony version at least partially in Leopold’s or Wolfgang’s hand, making clear that they themselves were involved in the redaction. In the remaining two cases (including the one at hand) we have only copyists’ manuscripts, but there seems every reason to believe (by analogy with the other three) that these too stem from originals coming from Mozart or his immediate circle. The symphony version of K. 62a was perhaps for use in Salzburg, but may also have been intended for Mozart’s first trip to Italy, begun on 13 December 1769. It was the Mozarts’ custom when travelling to give concerts in the cities they visited, both to promote Wolfgang’s reputation and to help finance the journey. We note, for instance, that Wolfgang gave public concerts in Innsbruck (17 December), Rovereto (25 December), Verona (5 January), Mantua (16 January), Milan (23 February), Bologna (26 March), Florence (2 April), etc. The programme in Mantua is known, and it included two symphonies by Mozart. The programmes of the other concerts have not come down to us, but some them undoubtedly also included symphonies. It was not until August 1770 that Mozart wrote home to Salzburg from Bologna announcing, “I have already composed four Italian symphonies”. This suggests that he had previously been using Salzburg symphonies brought along for the purpose, and K. 62a may well have been among them.

Concerning the first movement – a common-time allegro – Günter Hausswald has written of “the echoes of a festive, boisterous opera overture on the Italian model”. Characteristics of this style are, he continues, thematic material built on broken triads and fanfare-like ideas, as well as “a true al fresco style worked into a large-scale overall structure”. The melodies are “essentially conventional and traditional in scope”, and “limited to repeated broken chords; to rigidly maintained chains of scales; to instrumentally idiomatic, free figuration; to punctuating chords. Only two subsidiary ideas reveal an individual profile”. Lurking behind Hausswald’s description of the movement one senses disapproval of what he considered to be a lack of originality and of singable melody. But the 18th century was much more interested in suitability than in originality, and the lack of vocal melody places the movement in the category of abstract art, a category with which aestheticians of both the 18th and 20th centuries have had difficulties. In the former period Leopold Mozart referred to symphonies by J. Stamitz in the abstract vein as “nothing but noise”, and the writer Lacépède tried to cope with the problem by requiring that symphonies have programmes. Linguistic analogies, beloved of 20th-century analysts, which speak of phrases, sentences and paragraphs, break down in the face of works that would appear to be composed largely of conjunctions, prepositions and articles. Detlef Schultz dismisses such movements as “purely decorative” which, like Hausswald’s remarks, seems to hint at a perceived “lack of meaning”. Here we have an aspect of musical creativity in which practice has far outstripped the ability of theory to explain it.

The minuet that follows is also based upon fanfares and scales. Its opening idea seems tongue-in-cheek, perhaps because, as Machaut had a circular creation of his own proclaim, “Ma fin est mon commencement”. The trio, in G major and for strings alone with divided violas, offers us a chamber-music intimacy that contrasts happily with the pomp of the minuet.

The marvellous change of tone evident from the first note of the andante (in 2/4 and A major) is due to a combination of factors: the key changes; the horns, trumpets and kettledrums have dropped out; the violins are muted; the cellos and basses play pizzicato; and the oboists would here have put down their instruments and taken up transverse flutes. This pastoral movement is dominated by the sound of the flutes, whether sustaining slowly changing harmonies or adding melodic fillips.

A second minuet exhibits less pomp than the first, though with even more scales. The trio, again for strings alone but now in D minor, makes much of joking grace notes and the slapstick comedy of high versus low and loud versus soft. Hausswald calls the trio “scherzo-like”.

The finale, a jig in the form of a rondo, brings the festivities to a suitably lively conclusion. Its principal theme, which occurs no fewer than fourteen times, bears a passing resemblance to the popular German round Am Abend, the first line of which is “O wie wohl ist mir am Abend” and which in English-speaking countries is known by the words “O how lovely is the evening”. The author of this tune is said to be one K. Schulz. Can this be the Karl Schulz who was a tenor and voice teacher at the Salzburg Cathedral during the periods 1769-79 and 1783-87? On the other hand, the principal theme also resembles the hunting call entitled “Le vol-ce-l’est”. According to an 18th-century treatise on hunting, “One sounds this fanfare when one again sees the hunted stag”. The likelihood is that these three tunes are not directly related, but have common antecedents.

Symphony No.9 in C major, K. 73

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Menuetto & Trio

4. Allegro molto

The autograph manuscript of this work, also formerly in Berlin and now at Kraków, bears only the inscription “Sinfonie” in Mozart’s hand. The date “1769” was added in a later hand, perhaps Leopold’s. Köchel accepted that date and the editors of the sixth edition of his catalogue have reverted to the same date, thus calling into question Alfred Einstein’s assignment of the work in the third edition to the summer of 1771. It is due to Einstein’s attempted redating (accepted by Saint-Foix) that this symphony will occasionally be found designated as K. 75a. As a sketch for the minuet of this symphony is found in the autograph of a series of minuets (K. 61d/103) that Mozart is thought to have written for Carnival 1769, the symphony may have been completed around that time and the Köchel number 73 would therefore be too high. The error of Einstein’s proposed redating is confirmed by another manuscript, which originated as an attempt by Leopold to copy out a bass part for this symphony. For unknown reasons Leopold abandoned his effort after only 12 bars, and Wolfgang later used the largely empty sheet of music paper to resolve a puzzle canon from Padre Martini’s Storia della musica, a book which came into the Mozarts’ possession in early October 1770.